Recently, I studied in detail one of the most effective cryptographic attacks on the TLS handshake: the Logjam attack of 2015, published in a paper titled Imperfect Forward Secrecy: How Diffie-Hellman Fails in Practice. This article is an extension of a presentation I prepared on this topic, as part of a seminar course.

The talk tried to cover all the key concepts and methods required to fully understand the functioning and impact of this attack. It is divided into 5 broad sections: 1. a conceptual walkthrough (of the Diffie-Hellman key exchange, Number field sieve, TLS handshake, man-in-the middle attacks), 2. a description of the Logjam attack, its working, time costs and consequences, 3. Recommendations from the authors and mitigations implemented in TLS 1.3.

1. Overview

The attack targets the Diffie-Hellman key exchange part of the TLS handshake, and enables the adversary to break the protocol by performing a “downgrade” man-in-the-middle attack in the first step. Thereby, it reduces the Diffie-Hellman key size to 512-bits, which is then computable in real-time by the attacker. A server’s willingness to accept a connection with 512-bit Diffie-Hellman “export” keys is therefore a crucial enabler of this attack. Once the connection is downgraded, the attacker computes the server’s secret key, and hence also the master secret and session keys, and can then impersonate the server completely by forging the “Finished” message in the handshake. Another key loophole enabling the attack is therefore also the lack of the server’s signature on the cipher suite agreement message in the handshake.

A key mathematical tool used during this attack is the Number Field Sieve, which can compute discrete logarithms in the fastest known time, using a database of pre-computed values.

The attack was not only demonstrated theoretically, but also executed in practice on real websites on the internet. The authors demonstrated a devastating compromise of a large number of websites whose configured TLS protocol had not removed support for export-grade cryptography. The massive scale of the attack was caused by widespread reuse of a small set of DHE parameters across the internet and the ability of the attack to use precomputed values for the cryptanalysis.

2. Conceptual Walkthrough

Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange

The Diffie-Hellman key exchange is a method for two parties to agree on a shared secret key over an insecure communication channel. Following is a concise explanation of the process.

- Initial Parameters Setup: Both parties agree on a large prime number $p$ and a primitive root modulo $p$, denoted $g$. These parameters ($p$ and $g$) are public and can be freely shared.

- Private Key Generation: Each party independently generates a private key: Party A selects a private key $a$, Party B selects a private key $b$.

- Public Key Calculation:

- Both parties independently calculate a public key:

- Party A computes $K_A = g^a \mod p$. Party B computes $K_B = g^b \mod p$.

- Key Exchange: Parties exchange their public keys ($K_A$ and $K_B$).

- Shared Secret Key Derivation:

- Both parties independently derive the shared secret key using the received public key and their own private key: Party A computes $K = B^a \mod p$ and Party B computes $K’ = A^b \mod p$.

- Result: The calculated keys $K$ and $K’$ are identical and serve as the shared secret key.

It is computationally infeasible for an eavesdropper who intercepts the public keys exchanged to determine the shared secret key without knowledge of the private keys. In turn, to derive any of the private keys, an attacker needs to solve the Discete Logarithm Problem (DLP): Given group elements $g$ and $h = g^x$, compute the number $x$ (modulo the group order of $g$).

This problem is known and accepted to be computationally infeasible for large enough key sizes. More precisely, Shoup’s theorem states that any “generic” algorithm that solves the discrete logarithm problem in an arbitrary group $G$ of size $n$ must perform at least $\Omega(n^{1/2})$ group operations (exponential complexity). Here, “generic” means that the algorithm has access to the group structure only via two oracles: one for performing group operations and one for testing for equality in the group. In some elliptic curve groups, the generic algorithm is the best we can do. However, this is not so for finite field groups, where we can exploit the structure.

Number field sieve (NFS) for DLP

The Number Field Sieve is an instance of a more general method called index calculus. It solves the discrete logarithm problems in finite fields with heuristic subexponential, superpolynomial complexity.

Without going too much into the mathematics of its working, one may summarise the approach as follows. Given $h = g^x \mod p$, to compute this logarithm $x \mod (p-1)$, we first find discrete logarithms modulo large prime divisors $l$ of $p-1$, i.e., relations of the form $j = \log_g h \mod l$ and use the Chinese remainder theorem to find the original logarithm. The prime factorization of $p-1$ is typically known in most cryptographic contexts. If not, we can use the factorization version of the NFS to find it, which runs in the same time as this algorithm.

The index calculus method in general proceeds as follows. Let $h = g^x \mod p$. We want to calculate the integer $x$ modulo $(p-1)$. Fix a smoothness bound $B$.

-

Pick integer $i$ at random. Test divisibility of $h \cdot g^i$ by all primes below $B$. If $h \cdot g^i \mod p$ is $B$-smooth, keep the relation:

$h \cdot g^i = p_1^{e_1} \times \cdots \times p_k^{e_k} \mod p$.

-

Taking logs with base $g$ gives:

$x + i = e_1 \log_g p_1 + \cdots + e_k \log_g p_k \mod (p-1)$

-

Vary $i$ to obtain multiple such relations, until there are enough linear equations

-

Solve the linear system to find $x$ (and the logarithms of all elements of the factor base that appear in at least one relation) modulo a factor of $p-1$

-

Combine the solutions of multiple systems to get a solution modulo $p-1$

The Number Field Sieve, in turn, involves the following steps.

- Polynomial Selection: select a suitable rational polynomial $f(z)$ with a fixed degree defining a number field $\mathbb{Q}(z)/f(z)$. This step parallelizes well and is only a small portion of the runtime

- Sieving: find special pairs of integers that satisfy the polynomial $f(z)$

- factor integers in batches to find relations of elements whose prime factors modulo $p$ are $B$-smooth

- This step parallelizes well but is computationally expensive

- Matrix Step: construct a large, sparse matrix consisting of the coefficient vectors of prime factorizations found. The null space gives a database of the logs of many small elements

- Descent: deduce the discrete log of the target $h$: re-sieve until we can find a set of relations that allow us to write the log of $h$ in terms of the logs in the precomputed database. Three phases of sieving with decreasing prime size. The final phase reconstructs the target using the log database

For a group of size $n$, the complexity is given by

$$ \exp\left( (c + o(1))(\log n)^{1/3} (\log \log n)^{2/3} \right) $$

This depends on parameters like the degree of $f$, sieving region, and $B$.

Size of $p$ and export grade cryptography

As of 2023, $|p| = 2048$ for appropriate “safe” primes $p$ is considered sufficiently strong. In the 1990s, the U.S. government did not approve export of cryptographic products unless the key size was strictly limited, therefore breakable. This was in attempt to control foreign countries’ usage of cryptography. During this era, cryptographic products were divided into two classes: products with “strong” cryptography and products with “weak” (exportable) cryptography. The key sizes in “weak cryptography” were as follows:

- $\leq 56$ bits in symmetric algorithms,

- $\leq 512$ bits for RSA/Diffie-Hellman moduli

- $\leq 112$ bits for elliptic curve keys

To comply with 1990s-era U.S. export restrictions on cryptography, SSL 3.0 and TLS 1.0 supported reduced-strength DHE_EXPORT ciphersuites that were restricted to primes no longer than 512 bits. In January 2000, these restrictions on export regulations were dramatically relaxed. However, many libraries and servers retained support for the sake of backwards compatibility. Today, all cryptographic products are exportable without a license unless end-users are foreign governments or “embargoed destinations”. Export to governments may be approved under a license.

Man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks

In this type of attack, an attacker intercepts and potentially alters the data exchanged between two communicating parties without their knowledge. The two communicating parties do not suspect that their communication is being relayed. From their perspective, it appears as if they are communicating directly with each other. For this, the MITM must transmit data between the parties so that the communication appears as usual. Common targets are communication channels such as Wi-Fi networks, public hotspots, and unsecured websites. Some common techniques employed are as follows.

- Packet Sniffing: Attacker intercepts and analyze data packets as they travel across a network. Tools: Wireshark, tcpdump

- ARP Spoofing/Poisoning: Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) spoofing involves sending false ARP messages to link an attacker’s MAC address with the IP address of a legitimate party

- DNS Spoofing: Attackers can manipulate the DNS to redirect users to malicious websites.

- HTTP Session Hijacking: capturing session cookies, session IDs, or other authentication tokens.

- SSL Stripping: Forcing a connection to use HTTP instead of HTTPS where a website supports both

- Wi-Fi Eavesdropping: Setup of rogue Wi-Fi hotspots with names similar to legitimate networks.

- Email Hijacking: Compromising email accounts, Ex. by phishing

- Malicious Proxies: Users unknowingly using the proxy think they are connecting directly to the intended website.

- Rogue Devices: physical insertion of a rogue device (Ex. malicious router, switch) into a network to capture or manipulate data

The best mitigation technique to prevent MITM attacks is mutual authentication and data encryption, both of which are achieved typically using TLS.

TLS Handshake

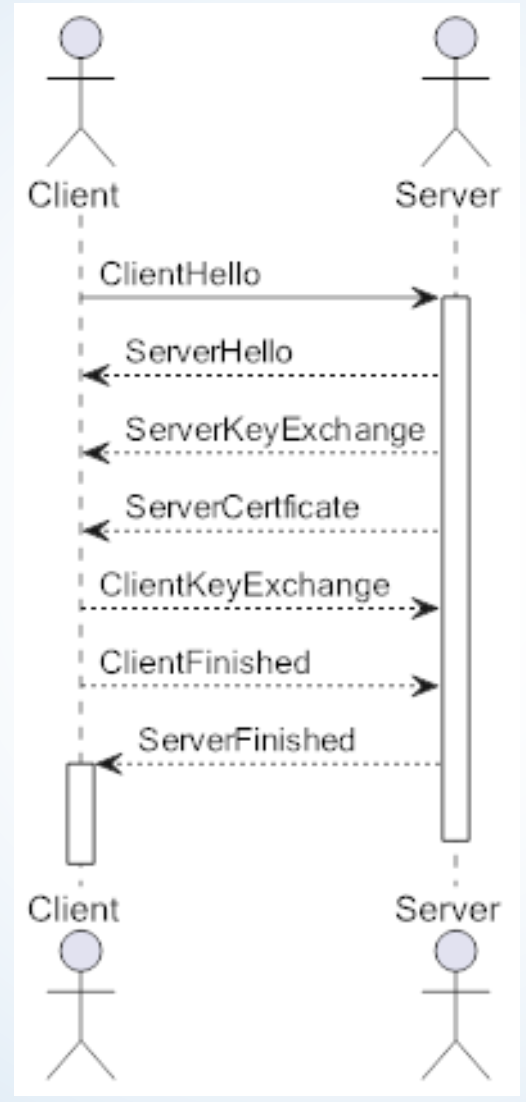

The TLS Handshake process can be summarised by the following diagram.

The following messages are involved in the handshake:

- ClientHello: protocol version, client random $cr$, optional session id to resume, a list of ciphersuites, list of compression methods, list of extensions

- ServerHello: selected protocol version, server random $sr$, session $id$, selected cipher suite, selected compression method, list of extensions

- Server certificate

- Server key generation and exchange: prime $p$, public key $g^b$, $\text{signature}(p, g, g^b, sr, cr)$

- Server Hello Done

- Client Key generation, exchange: public key $g^a$

- Client Key Calculation: $(ms, k_1, k_2) = \text{kdf}(cr, sr, g^a, b)$

- Server Key Calculation: $(ms, k_1, k_2) = \text{kdf}(cr, sr, g^a, b)$

- Client and Server Handshake Finished messages: To verify that the handshake was not tampered with, the client and server calculate the verification data: a MAC of the handshake transcript, and send it with the Finished messages

TLS $\leq $ 1.2 allowed fallback to DHE_EXPORT, enabling downgrade attacks like Logjam.

3. The Attack

Logjam is reminiscent of the recent FREAK attack, which relied on an implementation bug in RSA key exchange. It relies on a protocol flaw in TLS $\leq$ 1.2, namely its composition of the ephemeral Diffie-Hellman ciphersuites DHE and DHE_EXPORT. The downgrade attack involves forcing two participants to use the weakest cipher supported by both parties, so that the attacker can eventually calculate the key.

The fundamental underlying assumption is that only the server can continue the session with the client due to its knowledge of the secret key $b$ (therefore the ability to calculate the MAC and decrypt further messages).

The underlying vulnerability

The loophole exploited by this attack is the structure of the signed ServerKeyExchange message containing a 512-bit $p_{512}$ is identical to the message sent during standard DHE ciphersuites, i.e. the signature of the server does not attest to the negotiated ciphersuite.

$$ServerKeyExchange = [\text{prime } p, \text{public key } g^b, \text{signature}(p, g, g^b, sr, cr)]$$

An active MITM attacker can thereby rewrite the client’s ClientHello to DHE_EXPORT, remove other ciphersuites, and forward the ServerKeyExchange message to the client as is.

The client will verify the signature correctly and interpret the export-grade tuple $(p_{512}, g, g^b)$ as valid DHE parameters chosen by the server and proceed with the handshake. Note that this is possible because the initial handshake messages are sent over HTTP (before any encryption or authentication occurs).

Challenges for an attacker

- Handshake transcript mismatch Note that the client and server have different handshake transcripts (record of all exchanged messages) at the end. The Finished messages include the MAC of the handshake to verify that nothing was tampered with. If the Finished message from either party reaches the legitimate other party, it would become clear that the handshake was tampered with.

Solution: However, an attacker can work around this as follows. An attacker who can compute $b$ in close to real time can derive the master secret and connection keys, and therefore can compute a valid MAC of their own version of the handshake with the client, thereby completing the handshake with the client and terminating its connection with the server.

- Computing individual discrete logs in close to real time

Even 512-bit discrete logs are not straightforward to compute in real time.

Solution: An attacker performs NFS precomputations in advance for the two most popular 512-bit primes, and then downgrade the protocol to use 512-bit keys to allow for practical real-time computation of the secret key using NFS.

- Delaying handshake until log computation completes

Even after the downgrade attack, the computation of the discrete log still requires about a minute.

Solution: The following workarounds are available to an attacker:

- Non-browser clients: Different TLS clients impose different time limits for the handshake before killing the connection. Command-line clients like

curlandgitoften have long or no timeouts - TLS warning alerts: Web browsers have shorter timeouts. We can keep their connections alive by sending TLS warning alerts: ignored by the browser but reset the handshake timer

- Ephemeral key caching: Many TLS servers reuse their DH keys for multiple negotiations. An attacker can compute the discrete log of $g^b$ from one connection and use it to attack a later handshake. The authors found that 17% of IPv4 hosts reused $g^b$ at least once over the course of 20 handshakes, and that 15% only used one value

- TLS False Start: This extension reduces connection latency by having the client send early application data (such as an HTTP request) without waiting for the server’s Finished message to arrive

Time costs: 512-bit cryptanalysis

The NFS Precomputations performed by the authors took a little over 7 days for each prime. Each resulting database of known logs for the descent occupied about 2.5 GB in ASCII format. Further, computing individual logs in real time took a median of 70 seconds. This time varied actually between 34 and 206 seconds. The times were about the same for each prime.

Consequences

Since generating primes with special properties can be computationally burdensome, many implementations use fixed or standardized Diffie-Hellman parameters. For both normal and export-grade Diffie-Hellman, the vast majority of servers use a handful of common groups. The two 512-bit Diffie-Hellman groups they performed precomputations for were used by more than 92% of the vulnerable servers. This caused the computation of 512-bit Diffie-Hellman secret keys for two public keys sufficient to break a large proportion of websites on the internet. 82% of the vulnerable servers used a single 512-bit group, allowing compromised connections to 7% of Alexa Top Million HTTPS sites. Using the Logjam attack, an attacker with modest resources can hijack connections to approximately 1.6M SMTP, 429K IMAPS, and 454K POP3S email servers.

Other Weak and Misconfigured Groups

Apart from export-grade parameters, the authors discovered also the use of several other types of weak cryptography.

- 512-bit keys were used also for non-export DHE: 2,631 servers with browser-trusted certificates (and 118 in the Top 1M domains) used 512-bits in the non-export options. In these instances, active attacks may be unnecessary. If a browser negotiates a DHE ciphersuite with one of these servers, a passive eavesdropper can later compute the discrete log and obtain the TLS session keys for the connection.

- Non-safe primes: 4,800 of 70,000 distinct primes scanned were not safe, i.e., $(p - 1)/2$ was composite. Such primes are not necessarily vulnerable, as long as $g$ generates a group with at least one sufficiently large subgroup.

- Misconfigured groups: The Digital Signature Algorithm uses primes $p$ such that $p-1$ has a large prime factor $q$ and $g$ generates only a subgroup of order $q$. Some servers used Java’s DSA primes as $p$ but mistakenly used the DSA group order $q$ in the place of the generator $g$.

4. Author recommendations and mitigations in TLS 1.3

In order to protect TLS connections from the Logjam attack, the authors suggest a number of mitigations.

- Transition to elliptic curves

- Increase minimum key strengths: disable

DHE_EXPORTand configure DHE ciphersuites to use primes $\geq 2048$ bits. Browsers and clients should raise the minimum accepted size for Diffie-Hellman groups to at least 1024 bits in order to avoid downgrade attacks - Phase out 1024-bit DHE (and 1024-bit RSA) in the near term. Clients should raise the minimum DHE group size to 2048 bits as soon as server configurations allow. Server operators should move to $\geq 2048$-bit groups

- Avoid fixed-prime 1024-bit groups. When needed, generating fresh 1024-groups may help, but it is possible to create trapdoored primes that are computationally difficult to detect. At minimum, clients should check that servers’ parameters use safe primes or a verifiable generation process. Ideally, the process for generating and validating parameters in TLS should be standardized to thwart the risk of trapdoors

3. Author recommendations and mitigations in TLS 1.3:

- All legacy and dangerous functionality was removed from TLS version 1.3 (released ~2018): SHA-1, RC4, DES, 3DES, AES-CBC, MD5, vulnerable DH groups, weak export ciphers

- The server signature is now on the entire handshake transcript up to that point, so the Finished message can no longer be forged

- No more take-out menu: The colossal set of combinations that was allowed for negotiation of cipher suites in TLS 1.2 is replaced by a much more compact set in TLS 1.3